فهرست دادارباوران

(تغییرمسیر از فهرست خداانگاران)

این فهرست مختصری از کسانی است که خدا (دادارباور) شناخته شدهاند، این عقیده باور به خدا بر اساس الهیات طبیعی است.

- آبراهام لینکلن (۱۸۰۹–۱۸۶۵)، ۱۶ امین رئیسجمهور ایالات متحده آمریکا.[۱][۲]

- آدام اسمیت (۱۷۲۳–۱۷۹۰)، فیلسوف و اقتصاددان اسکاتلندی، پدر اقتصاد مدرن.[۳]

- آناکساگوراس (۵۰۰ ق. م-۴۲۸ ق. م)، فیلسوف پیشاسقراطی یونانی.[۴]

- آنتونی فلو (۱۹۲۳–۲۰۱۰)، فیلسوف بریتانیایی و بیخدای سابق مشهور.[۵]

- آندره ساخاروف (۱۹۲۱–۱۹۸۹)، فیزیکدان هستهای شوروی، دگراندیش و فعال حقوق بشر.[۶]

- آیزاک نیوتن (۱۶۴۲–۱۷۲۷)، فیزیکدان، ریاضیدان و اخترشناس انگلیسی.[۷][۸][۹][۱۰]

- ابن رشد (۱۱۲۶–۱۱۸۹)، علامه اندلسی، استاد ارسطوگری و فلسفه اسلامی، ریاضی، ستارهشناسی و دیگر علوم[۱۱][۱۲]

- ابوالعلاء معری (۹۷۳–۱۰۵۸)، فیلسوف نابینای عرب، شاعر، نویسنده و خردگرا.[۱۳]

- احمد کسروی (۱۸۹۰–۱۹۴۶)، زبانشناس و مورخ ایرانی.[۱۴]

- ارسطو (۳۸۴ ق. م-۳۲۲ ق. م)، فیلسوف یونان باستان فلسفه و علامه، شاگرد افلاطون و آموزگار اسکندر.[۱۵][۱۶][۱۷]

- ارنست رادرفورد (۱۸۷۱–۱۹۳۷)، شیمیدان نیوزیلندی، پدر فیزیک هستهای.[۱۸][۱۹]

- الکساندر پوپ (۱۶۸۸–۱۷۴۴)، شاعر انگلیسی قرن هجدهم.

- ایتن آلن (۱۷۳۸–۱۷۸۹)، انقلابی و رهبر چریکی در آمریکای اولیه.[۲۰]

- بنجامین فرانکلین (۱۷۰۶–۱۷۹۰)، دانشمند همهچیزدان آمریکایی، از پدران بنیانگذار ایالات متحده آمریکا[۲۱]

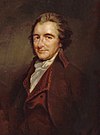

- تامس پین (۱۷۳۷–۱۸۰۹)، نویسنده انقلابی انگلیسی از پدران بنیانگذار ایالات متحده آمریکا.[۲۲]

- تامس جفرسون (۱۷۴۳–۱۸۲۶)، از پدران بنیانگذار آمریکا، نویسنده اصلی اعلامیه استقلال ایالات متحده آمریکا.[۲۳][۲۴][۲۵]

- توپاک شکور (۱۹۷۱–۱۹۹۶)، رپر، بازیگر و فعال آمریکایی.

- توماس ادیسون (۱۸۴۷–۱۹۳۱)، مخترع و بازرگان آمریکایی.[۲۶]

- جان لاک (۱۶۳۲–۱۷۰۴)، فیلسوف برجسته انگلیسی در زمینه تجربهگرایی.[۲۷]

- جورج واشینگتن (۱۷۳۲–۱۷۹۹)، یکی از پدران بنیانگذار ایالات متحده آمریکا، و اولین رئیسجمهور آمریکا.[۲۸]

- جیمز مدیسون (۱۷۵۱–۱۸۳۶)، «پدر قانون اساسی ایالات متحده آمریکا»، یکی از پدران بنیانگذار ایالات متحده آمریکا، ۴امین رئیسجمهور آمریکا.[۲۸]

- جیمز وات (۱۷۳۶–۱۸۱۹)، مخترع و مهندس مکانیک اسکاتلندی، از آغازگران انقلاب صنعتی.[۲۹][۳۰]

- چارلز سندرز پرس (۱۸۳۹–۱۹۱۴)، فیلسوف و منطقدان آمریکایی، پدر عملگرایی.[۳۱]

- چارلز لایل (۱۷۹۷–۱۸۷۵)، وکیل بریتانیایی و از مهمترین زمینشناسان عصر خود.[۳۲]

- دیمیتری مندلیف (۱۸۳۴–۱۹۰۷)، شیمیدان و مخترع روسی، مبدع اولین جدول تناوبی عناصر.[۳۳]

- رابرت هوک (۱۶۳۵–۱۷۰۳)، فیلسوف طبیعی و دانشمند همهچیزدان انگلیسی.[۳۴]

- زکریای رازی (۸۶۵–۹۲۵)، علامه، فیلسوف، پزشک و محقق ایرانی.[۳۵]

- ژان لروند دالامبر (۱۷۱۷–۱۷۸۳)، ریاضیدان و فیلسوف فرانسوی، او به همراه دنی دیدرو آنسیکلوپدی را نوشت.[۳۶]

- ژان-باتیست لامارک (۱۷۴۴–۱۸۲۹)، طبیعیدان و زیستشناس فرانسوی، از اولین نظریهپردازان فرگشت.[۳۷]

- ژول ورن (۱۸۲۸–۱۹۰۵)، نویسنده پیشتاز علمی–تخیلی فرانسوی، نویسنده رمانهایی چون بیست هزار فرسنگ زیر دریا، و دور دنیا در هشتاد روز.[۳۸]

- سیسرون (۱۰۶ ق. م-۴۳ ق. م)، سیاستمدار رومی، نظریهپرداز سیاسی و فیلسوف.[۳۹]

- سیمون نیوکامب (۱۸۳۵–۱۹۰۹)، ریاضیدان و ستارهشناس کانادایی-آمریکایی.[۴۰]

- فریدریش دوم (۱۷۱۲–۱۷۸۶)، شاه پروسی از خاندان هوهنتسولرن.[۴۱]

- فریدریش شیلر (۱۷۵۹–۱۸۰۵)، شاعر، فیلسوف، نویسنده و مورخ آلمانی.[۴۲]

- کارل فریدریش گاوس (۱۷۷۷–۱۸۵۵)، ریاضیدان و فیزیکدان آلمانی.[۴۳][۴۴][۴۵][۴۶]

- کولین مکلورین (۱۶۸۹–۱۷۴۶)، ریاضیدان اسکاتلندی.[۴۷]

- گوتفرید لایبنیتس (۱۶۹۴–۱۷۱۶)، فیلسوف و ریاضیدان آلمانی.[۴۸]

- گوتهولد افرایم لسینگ (۱۷۲۹–۱۷۸۱)، فیلسوف، منتقد و نویسنده آلمانی.[۴۹]

- لئوناردو دا وینچی (۱۴۲۵–۱۵۱۹)، نقاش، معمار، موسیقیدان و دانشمند رنسانس ایتالیایی.[۵۰][۵۱]

- لوئیس والتر آلوارز (۱۹۱۱–۱۹۸۸)، فیزیکدان نظری آمریکایی برنده جایزه نوبل فیزیک.[۵۲]

- لودویگ بولتزمان (۱۸۴۴–۱۹۰۶)، فیزیکدان اتریشی از پایهگذاران مکانیک آماری.[۵۳][۵۴]

- مارتین گاردنر (۱۹۱۴–۲۰۱۰)، ریاضیدان آمریکایی و نویسنده علم به زبان ساده، با علاقه به شکگرایی علمی.[۵۵]

- ماکس برن (۱۸۸۲–۱۹۷۰)، فیزیکدان و ریاضیدان آلمانی-بریتانیایی.[۵۶][۵۷]

- ماکس پلانک (۱۸۵۸–۱۹۴۷)، فیزیکدان آلمان، بنیانگذار فیزیک کوانتومی.[۵۸]

- ماکسیمیلیان روبسپیر (۱۷۵۸–۱۷۹۴)، انقلابی فرانسوی و حقوقدان.[۵۹]

- موسی مندلسون (۱۷۲۹–۱۷۸۶)، فیلسوف آلمانی.[۶۰]

- میخاییل لومونسف (۱۷۱۱–۱۷۶۵)، دانشمند و نویسنده روسی.[۶۱]

- ناپلئون بناپارت (۱۷۶۹–۱۸۲۱)، رهبر سیاسی و نظامی فرانسوی.[۶۲]

- نیک کیو (۱۹۵۷-)، موسیقیدان، نویسنده و بازیگر استرالیایی.[۶۳][۶۴]

- نیل آرمسترانگ (۱۹۳۰–۲۰۱۲)، فضانورد ناسا، اولین انسان قدم گذاشته بر سطح ماه.[۶۵]

- هامفری دیوی (۱۷۷۸–۱۹۲۹)، شیمیدان نوآور بریتانیایی.[۶۶]

- ورنر فون براون (۱۹۱۲–۱۹۷۷)، مهندس هوافضای آلمانی-آمریکایی، از پیشتازان فناوری راکت.[۶۷]

- ورنر کارل هایزنبرگ (۱۹۰۱–۱۹۷۶)، فیزیک نظری آلمانی برنده جایزه نوبل فیزیک، شناختهشده برای اصل عدم قطعیت.[۶۸][۶۹]

- ولتر (۱۶۹۴–۱۷۷۸)، فیلسوف عصر روشنگری فرانسه.[۷۰]

- ویکتور هوگو (۱۸۰۲–۱۸۸۵)، نویسنده و هنرمند فرانسوی.[۷۱][۷۲]

- ویلیام هوگارت (۱۶۹۷–۱۷۶۴)، نقاش و هنرمند تجسمی انگلیسی[۷۳]

- پیتبول خواننده و آهنگ ساز مشهور کوبایی-امریکایی

جستارهای وابسته ویرایش

منابع ویرایش

- ↑ Michael Lind (۲۰۰۶). What Lincoln Believed: The Values and Convictions of America's Greatest President. Random House Digital, Inc. ص. ۴۸. شابک ۹۷۸-۱-۴۰۰۰-۳۰۷۳-۶.

Lincoln was known to friends and enemies alike throughout his life as a deist, a feet that illustrates the influence of eighteenth-century thought on his outlook. "I am not a Christian," he told Newton Bateman, the superintendent of education in Illinois.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ John B. Remsburg. Abraham Lincoln: Was He a Christian?. Library of Alexandria. شابک ۹۷۸-۱-۴۶۵۵-۱۸۹۴-۱.

Washington, like Lincoln, has been claimed by the church; yet, Washington, like Lincoln, was a Deist. This is admitted even by the leading churchmen of his day.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ The Times obituary of Adam Smith

- ↑ John Ferguson (ویراستار). Plato: Republic Book X. Taylor & Francis. ص. ۱۵.

Anaxagoras was a typical Deist.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Atheist Becomes Theist - Biola News and communications

- ↑ Sakharov believed that a non-scientific "guiding principle" governed the universe and human life. Drell, Sidney D. , and Sergei P. Kapitsa (eds.), Sakharov Remembered, pp. 3, 92. New York: Springer, 1991.

- ↑ James E. Force, Richard Henry Popkin, ویراستار (۱۹۹۰). Essays on the Context, Nature, and Influence of Isaac Newton's Theology. Springer. ص. ۵۳. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۷۹۲۳-۰۵۸۳-۵.

Newton has often been identified as a deist. ...In the 19th century, William Blake seems to have put Newton into the deistic camp. Scholars in the 20th-century have often continued to view Newton as a deist. Gerald R. Cragg views Newton as a kind of proto-deist and, as evidence, points to Newton's belief in a true, original, monotheistic religion first discovered in ancient times by natural reason. This position, in Cragg's view, leads to the elimination of the Christian revelation as neither necessary nor sufficient for human knowledge of God. This agenda is indeed the key point, as Leland describes above, of the deistic program which seeks to "set aside" revelatory religious texts. Cragg writes that, "In effect, Newton ignored the claims of revelation and pointed in a direction which many eighteenth-century thinkers would willingly follow." John Redwood has also recently linked anti-Trinitarian theology with both "Newtonianism" and "deism."

از پارامتر ناشناخته|coauthors=صرف نظر شد (|author=پیشنهاد میشود) (کمک); پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Suzanne Gieser. The Innermost Kernel: Depth Psychology and Quantum Physics. Wolfgang Pauli's Dialogue with C.G. Jung. Springer. صص. ۱۸۱–۱۸۲. شابک ۹۷۸-۳-۵۴۰-۲۰۸۵۶-۳.

Newton seems to have been closer to the deists in his conception of God and had no time for the doctrine of the Trinity. The deists did not recognize the divine nature of Christ. According to Fierz, Newton's conception of God permeated his entire scientific work: God's universality and eternity express themselves in the dominion of the laws of nature. Time and space are regarded as the 'organs' of God. All is contained and moves in God but without having any effect on God himself. Thus space and time become metaphysical entities, superordinate existences that are not associated with any interaction, activity or observation on man's part.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Joseph L. McCauley (۱۹۹۷). Classical Mechanics: Transformations, Flows, Integrable and Chaotic Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. ص. ۳. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۵۲۱-۵۷۸۸۲-۰.

Newton (1642-1727), as a seventeenth century nonChristian Deist, would have been susceptible to an accusation of heresy by either the Anglican Church or the Puritans.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Hans S. Plendl, ویراستار (۱۹۸۲). Philosophical problems of modern physics. Reidel. ص. ۳۶۱.

Newton expressed the same conception of the nature of atoms in his deistic view of the Universe.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Francesca Aran Murphy (۲۰۰۴). Art and Intellect in the Philosophy of Étienne Gilson. University of Missouri Press. ص. ۱۷۹. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۸۲۶۲-۱۵۳۶-۹.

But when thirteenth-century Parisian philosophers were atheists, Gilson said, “the deism of Averroës was their natural philosophy”:...

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ John Watkins (۱۸۰۰). An Universal biographical and historical dictionary: containing a faithful account of the lives, actions, and characters of the most eminent persons of all ages and all countries: also the revolutions of states, and the successions of sovereign princes, ancient and modern. R. Phillips.

...for Averroes was in fact a deist, and equally ridiculed the christian, jewish, and mohammedan religions.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Freethought Traditions in the Islamic World بایگانیشده در ۱۴ فوریه ۲۰۱۲ توسط Wayback Machine by Fred Whitehead; also quoted in Cyril Glasse, (2001), The New Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 278. Rowman Altamira.

- ↑ V. Minorsky. Mongol Place-Names in Mukri Kurdistan (Mongolica, 4), Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 58-81 (1957), p. 66. <58:MPIMK(>2.0.CO;2-# JSTOR

- ↑ Henry C. Vedder. Forgotten Books. ص. ۳۵۳. شابک ۹۷۸-۱-۴۴۰۰-۷۳۴۲-۷.

To use modern nomenclature, Plato is theist, Aristotle Deist.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Charles Bigg. Neoplatonism. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. ص. ۵۰.

The reason for this low-pitched morality Atticus discerned, and here again he was right, in the Deism of Aristotle. Deism regards God as creating and equipping the world, and then leaving it to itself.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Gary R. Habermas, David J. Baggett, ویراستار (۲۰۰۹). Did the Resurrection Happen?: A Conversation With Gary Habermas and Antony Flew. InterVarsity Press. ص. ۱۰۵. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۸۳۰۸-۳۷۱۸-۲.

While he mentioned evil and suffering, I did wonder about Tony's juxtaposition of choosing either Aristotle's Deism or the freewill defense, which he thinks “depends on the prior acceptance of a framework of divine revelation.

از پارامتر ناشناخته|coauthors=صرف نظر شد (|author=پیشنهاد میشود) (کمک); پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Michael Patrick Leahy (۲۰۰۷). Letter to an Atheist. Harpeth River Press. ص. ۵۵. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۹۷۹۴۹۷۴-۰-۷. پارامتر

|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Peter J. Bowler (۲۰۱۲). Reconciling Science and Religion: The Debate in Early-Twentieth-Century Britain. University of Chicago Press. ص. ۶۱. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۲۲۶-۰۶۸۵۹-۶.

Ernest Rutherford seems to have abandoned his Presbyterian up- bringing completely, apart from its moral code. A colleague wrote of him: "I knew Rutherford rather well and under varied conditions from 1903 onwards, but never heard religion discussed; nor have I found in his papers one line of writing connected with it." ...Given the reports quoted above, it is difficult to believe that either Rutherford or Ford was deeply religious in private.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Ethan Allen (۱۷۸۴). «Reason: The Only Oracle Of Man». بایگانیشده از اصلی در ۱۰ دسامبر ۲۰۰۴. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۳-۰۲-۰۷.

- ↑ The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin from earlyamerica.com

- ↑ «Modern History Sourcebook: Thomas Paine: Of the Religion of Deism Compared with the Christian Religion». Fordham.edu. بایگانیشده از اصلی در ۱۴ اوت ۲۰۱۴. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۰-۰۷-۰۴.

- ↑ «Jefferson's Religious Beliefs». monticello.org. Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۳-۰۲-۰۷.

- ↑ Michael Corbett and Julia Mitchell Corbett, Politics and religion in the United States (1999) p. 68

- ↑ Dulles، Avery (ژانویه ۲۰۰۵). «The Deist Minimum». First Things: A Monthly Journal of Religion and Public Life (۱۴۹): ۲۵ff.

- ↑ In a correspondence on the matter Edison said: "You have misunderstood the whole article, because you jumped to the conclusion that it denies the existence of God. There is no such denial, what you call God I call Nature, the Supreme intelligence that rules matter. All the article states is that it is doubtful in my opinion if our intelligence or soul or whatever one may call it lives hereafter as an entity or disperses back again from whence it came, scattered amongst the cells of which we are made." New York Times. October 2, 1910, Sunday.

- ↑ «MICHAEL J. THOMPSON - JOHN LOCKE IN JERUSALEM - LOGOS 4.1 WINTER 2005». Logosjournal.com. بایگانیشده از اصلی در ۳ اكتبر ۲۰۱۳. دریافتشده در 2010-07-04. تاریخ وارد شده در

|archive-date=را بررسی کنید (کمک) - ↑ ۲۸٫۰ ۲۸٫۱ «VQR" The Religion of James Monroe». Vqronline.org. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۰-۰۷-۰۴.

- ↑ Joseph McCabe (۱۹۴۵). A Biographical Dictionary of Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Freethinkers. Haldeman-Julius Publications. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۲-۰۶-۳۰.

- ↑ James Watt and the steam engine: the memorial volume prepared for the Committee of the Watt centenary commemoration at Birmingham 1919. Clarendon press. ۱۹۲۷. ص. ۷۸.

It is difficult to say anything as to Watt's religious belief, further than that he was a Deist.

از پارامتر ناشناخته|coauthors=صرف نظر شد (|author=پیشنهاد میشود) (کمک); پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Joseph Brent (۱۹۹۸). Charles Sanders Peirce: A Life (ویراست ۲). Indiana University Press. ص. ۱۸. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۲۵۳-۲۱۱۶۱-۳.

Peirce had strong, though unorthodox, religious convictions. Although he was a communicant in the Episcopal church for most of his life, he expressed contempt for the theologies, metaphysics, and practices of established religions.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Keith Stewart Thomson (۲۰۰۹). The Young Charles Darwin. Yale University Press. ص. ۱۰۹. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۳۰۰-۱۳۶۰۸-۱.

In his religious views, Lyell was essentially a deist, holding the position that God had originally created the world and life on it, and then had allowed nature to operate according to its own (God-given) natural laws, rather than constantly intervening to direct and shape the course of all history.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Michael D. Gordin (۲۰۰۴). A Well-ordered Thing: Dmitrii Mendeleev And The Shadow Of The Periodic Table. Basic Books. ص. ۲۳۰. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۴۶۵-۰۲۷۷۵-۰.

Mendeleev's son Ivan later vehemently denied claims that his father was devoutly Orthodox: "I have also heard the view of my father's 'church religiosity' — and I must reject this categorically. From his earliest years Father practically split from the church — and if he tolerated certain simple everyday rites, then only as an innocent national tradition, similar to Easter cakes, which he didn't consider worth fighting against." ...Mendeleev's opposition to traditional Orthodoxy was not due to either atheism or a scientific materialism. Rather, he held to a form of romanticized deism.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Robert Hooke and the English Renaissance. Gracewing Publishing. ۲۰۰۵. صص. ۲۶–۲۷. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۸۵۲۴۴-۵۸۷-۷.

It seems possible that the mature Hooke may have been something of a Deist: a man who believed in and revered the Great Creator God, but who may have been quietly sceptical on such points as the Incarnation, the Resurrection, and the Sacraments. But very importantly, he seems to have kept his inner thoughts to himself, and probably steered clear of religious questions even when drinking coffee with friends who were deans and bishops. ...One suspects, however, that the undisclosed privacy of Robert Hooke's personal beliefs on matters of religion was best summed up by Waller when he said: 'If he was particular in some Matters, let us leave him to the searcher of Hearts.'

از پارامتر ناشناخته|coauthors=صرف نظر شد (|author=پیشنهاد میشود) (کمک); پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Jennifer Michael Hecht, "Doubt: A History: The Great Doubters and Their Legacy of Innovation from Socrates and Jesus to Thomas Jefferson and Emily Dickinson", pg. 227-230

- ↑ "The dividing line between Deism and atheism among the Philosophes was often rather blurred, as is evidenced by Le Rêve de d'Alembert (written 1769; "The Dream of d'Alembert"), which describes a discussion between the two "fathers" of the Encyclopédie: the Deist Jean Le Rond d'Alembert and the atheist Diderot." Andreas Sofroniou, Moral Philosophy, from Hippocrates to the 21st Aeon, page 197.

- ↑ History of Paradise: The Garden of Eden in Myth and Tradition. University of Illinois Press. ۲۰۰۰. ص. ۲۲۳. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۲۵۲-۰۶۸۸۰-۵.

Like Erasmus Darwin and unlike Cabanis, Lamarck was a deist.

از پارامتر ناشناخته|coauthors=صرف نظر شد (|author=پیشنهاد میشود) (کمک); پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Frederick Paul Walter, ویراستار (۲۰۱۲). «Jules Verne, Ghostbuster». The Sphinx of the Ice Realm: The First Complete English Translation ; with the Full Text of The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym by Edgar Allan Poe. SUNY Press. ص. ۴۰۶. شابک ۹۷۸-۱-۴۳۸۴-۴۲۱۱-۲.

And despite what some have said, Verne isn't much different. His early biographers laid stress on his Roman Catholicism—his grandson (Jules-Verne, 63) called him “deistic to the core, thanks to his upbringing”—yet his novels rarely have any spiritual content other than a few token appeals to the almighty.

از پارامتر ناشناخته|coauthors=صرف نظر شد (|author=پیشنهاد میشود) (کمک); پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Deism بایگانیشده در ۲ اکتبر ۲۰۰۸ توسط Wayback Machine - Entry in the Dictionary of the History of Ideas

- ↑ James R. Wible (آوریل ۲۰۰۹). «Economics, Christianity, and Creative Evolution: Peirce, Newcomb, and Ely and the Issues Surrounding the Creation of the American Economic Association in the 1880s» (PDF). ص. ۴۳. بایگانیشده از اصلی (PDF) در ۲۲ ژوئیه ۲۰۱۳. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۲-۰۶-۰۵.

While rejecting all of the organized religions of human history, Newcomb does recognize that religious ideas are basic to the human mind. He articulates his point: “But there is a second truth admitted with nearly equal unanimity .... It is that man has religious instincts – is, in short, a religious animal, and must have some kind of worship. ” 51 What Newcomb wants is a new religion compatible with the best science and philosophy of his time. He begins to outline this new religion with doctrines that it must not have: 1. It cannot have a God living and personal.... 2. It cannot insist on a personal immortality of the soul.... 3. There must be no terrors drawn from a day of judgment.... 4. There can be no ghostly sanctions or motives derived from a supernatural power, or a world to come.... 5. Everything beyond what can be seen must be represented as unknown and unknowable.... (Newcomb 1878, p. 51).

- ↑ «Frederick the Great - Hyperhistory.net». بایگانیشده از اصلی در ۲۱ اوت ۲۰۰۹. دریافتشده در ۴ آوریل ۲۰۱۳.

- ↑ Victoria Frede (۲۰۱۱). Doubt, Atheism, and the Nineteenth-Century Russian Intelligentsia. University of Wisconsin Pres. ص. ۵۷. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۲۹۹-۲۸۴۴۴-۲.

Schiller was no atheist: he preached faith in God and respect for the Bible, but he condemned Christianity (both Catholic and Protestant forms) as a religion of hypocrisy.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Walter Kaufmann Bühler (۱۹۸۱). Gauss: A Biographical Study. Springer-Verlag. ص. ۱۵۳. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۳۸۷-۱۰۶۶۲-۵.

Judging from the correspondence, Gauss did not believe in a personal god. An essential part of his credo was his confidence in the harmony and integrity of the grand design of the creation. Mathematics was the key to man's efforts to obtain at least a faint idea of God's plan. Obviously, Gauss's beliefs had a strong resemblance to Leibniz's system, though they were much less systematic and explicit.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Gerhard Falk (۱۹۹۵). American Judaism in Transition: The Secularization of a Religious Community. University Press of America. ص. ۱۲۱. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۷۶۱۸-۰۰۱۶-۳.

Evidently, Gauss was a Deist with a good deal of skepticism concerning religion but incorporating a great deal of philosophical interests in the Big Questions, that is. the immortality of the soul, the afterlife and the meaning of man's existence.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ «Gauss, Carl Friedrich». Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. ۲۰۰۸. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۲-۰۷-۲۹.

In seeming contradiction, his religious and philosophical views leaned toward those of his political opponents. He was an uncompromising believer in the priority of empiricism in science. He did not adhere to the views of Kant, Hegel and other idealist philosophers of the day. He was not a churchman and kept his religious views to himself. Moral rectitude and the advancement of scientific knowledge were his avowed principles.

- ↑ Morris Kline (۱۹۸۲). Mathematics: The Loss of Certainty. Oxford University Press. ص. ۷۳. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۱۹-۵۰۳۰۸۵-۳. پارامتر

|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Jack Repcheck (۲۰۱۰). The Man Who Found Time: James Hutton and the Discovery of the Earth's Intiquity. ReadHowYouWant.com. ص. ۵۸. شابک ۹۷۸-۱-۴۵۸۷-۶۶۶۲-۵.

But Maclaurin had one other major effect on Hutton. Maclaurin was a deist, one who believes in a creator God, a God who designed and built the universe and then set His creation into motion (but does not interfere with the day-to-day workings of the system or the actions of people).

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ "Consistent with the liberal views of the Enlightenment, Leibniz was an optimist with respect to human reasoning and scientific progress (Popper 1963, p.69). Although he was a great reader and admirer of Spinoza, Leibniz, being a confirmed deist, rejected emphatically Spinoza's pantheism: God and nature, for Leibniz, were not simply two different "labels" for the same "thing". Shelby D. Hunt, Controversy in marketing theory: for reason, realism, truth, and objectivity (2003), page 33.

- ↑ «نسخه آرشیو شده». بایگانیشده از اصلی در ۱۳ فوریه ۲۰۰۹. دریافتشده در ۴ آوریل ۲۰۱۳.

- ↑ The Templar Code For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. ۲۰۰۷. ص. ۲۵۶. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۴۷۰-۱۲۷۶۵-۰.

Da Vinci was definitely an esoteric character and a man of contrasts; a bastard son who rose to prominence; an early Deist who worshipped the perfect machine of nature to such a degree that he wouldn't eat meat, but who made his first big splash designing weapons of war; a renowned painter who didn't much like painting, and often didn't finish them, infuriating his clients; and a born engineer who loved nothing more than hours spent imagining new contraptions of every variety.

از پارامتر ناشناخته|coauthors=صرف نظر شد (|author=پیشنهاد میشود) (کمک); پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Eugène Müntz (۲۰۱۱). Leonardo Da Vinci. Parkstone International. ص. ۸۰. شابک ۹۷۸-۱-۷۸۰۴۲-۲۹۵-۴.

To begin with, even if it could be shown – and this is precisely one of the points most in dispute – that Leonardo had broken with the teachings of the Catholic Church, it would still be nonetheless certain that he was a deist and not an atheist or materialist.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Alvarez: adventures of a physicist. Basic Books. ۱۹۸۷. ص. ۲۷۹. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۴۶۵-۰۰۱۱۵-۶.

To me the idea of a Supreme Being is attractive, but I'mjmre that such a Being isn't the one described in any holy book.

از پارامتر ناشناخته|coauthors=صرف نظر شد (|author=پیشنهاد میشود) (کمک); پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Ludwig Boltzmann: His Later Life and Philosophy, 1900-1906. The philosopher. Springer. ۱۹۹۵. ص. ۳. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۷۹۲۳-۳۴۶۴-۴.

Boltzmann's tendency to think that the methods of theoretical physics could be applied to all fields with profit both within and outside of science apparently made it difficult for him to sympathize with most religion. His own religious position as given above seems to emphasize hope rather than belief, as if he hoped that good luck would come to him without specifying whether this would be caused by Divine Intervention, Divine Providence, or by natural or historical forces not yet understood by science or whose occurance or timing one could not yet predict. But in the same letter to Brentano he maintains: "I pray to my God just as ardently as a priest does to his."

از پارامتر ناشناخته|coauthors=صرف نظر شد (|author=پیشنهاد میشود) (کمک); پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Ludwig Boltzmann: His Later Life and Philosophy, 1900-1906. The philosopher. Springer. ۱۹۹۵. ص. ۴. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۷۹۲۳-۳۴۶۴-۴.

Boltzmann in optimistic moods liked to think of himself as an idealist in the sense of having high ideals and a materialist in all three major senses enjoying the material world, opposing spiritualist philosophy, and reducing reality to matter... Boltzmann may not have been an ontological materialist, at least not in a classical sense and not in his methodology of science but rather closer to the phenomenalistic positions normally associated with David Hume and Ernst Mach.

از پارامتر ناشناخته|coauthors=صرف نظر شد (|author=پیشنهاد میشود) (کمک); پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Dale Essary. «A Review of Martin Gardner's 'Did Adam and Eve Have Navels? Discourses on Reflexology, Numerology, Urine Therapy, and Other Dubious Subjects'». بایگانیشده از اصلی در ۲۴ سپتامبر ۲۰۱۵. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۲-۰۷-۱۸.

Gardner is a fideist, a particular kind of deist who believes that God, though he exists, is unknowable and has not bothered to make himself known to mankind through any means of divine intervention or revelation. The topic for which Gardner exposes his amateurish grasp is biblical exegesis, for which his sophomoric approach should be an embarrassment to a man of his tenure. The title alone of the book under discussion lets us know that Gardner cannot help but take a few cheap shots at that lunatic fringe sect known as “fundamentalist” Christianity.

- ↑ Nancy Thorndike Greenspan (۲۰۰۵). The End of the Certain World: The Life and Science of Max Born: the Nobel Physicist who Ignited the Quantum Revolution. Basic Books. صص. ۵۸–۶۲. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۷۳۸۲-۰۶۹۳-۶.

Max later traced his reluctance to his father, who had taught him not to believe in a God who punished, rewarded, or performed miracles. Like his father, he based his morality on his "own conscience and on an understanding of human life within a framework of natural law." ...Born, in fact, was no longer Jewish. His mother-in-law had worn him down. In March 1914, after a few religion lessons in Berlin, he was baptized a Lutheran by the pastor who had married him to Hedi. As he later explained, "there were...forces pulling in the opposite direction [to my own feelings]. The strongest of these was the necessity of defending my position again and again, and the feeling of futility produced by these discussions [with Hedi and her mother]. In the end I made up my mind that a rational being as I wished to be, ought to regard religious professions and churches as a matter of no importance.... It has not changed me, yet I never regretted it. I did not want to live in a Jewish world, and one cannot live in a Christian world as an outsider. However, I made up my mind never to conceal my Jewish origin."

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Rit Nosotro (۲۰۰۳). «Max Born». HyperHistory.net. بایگانیشده از اصلی در ۲۶ آوریل ۲۰۱۳. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۲-۰۶-۱۹.

In 1912 Max married a descendent of Martin Luther named Hedi. They were married by a Lutheran pastor who two years later would baptize Max into the Christian faith. Far from being a messianic Jew who fell in love with Rabbi Yeshua (Jesus), Max was merely one of the millions of Jews who no considered assimilation of more importance than their Jewish faith. As Max explained, "there were...forces pulling in the opposite direction [to my own feelings]. The strongest of these was the necessity of defending my position again and again, and the feeling of futility produced by these discussions [with Hedi and her mother]. In the end I made up my mind that a rational being as I wished to be, ought to regard religious professions and churches as a matter of no importance.... It has not changed me, yet I never regretted it. I did not want to live in a Jewish world, and one cannot live in a Christian world as an outsider. However, I made up my mind never to conceal my Jewish origin."

- ↑ J. L. Heilbron (۱۹۸۶). The Dilemmas of an Upright Man: Max Planck and the Fortunes of German Science. Harvard University Press. ص. ۱۹۸. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۶۷۴-۰۰۴۳۹-۹.

On the other side, Church spokesmen could scarcely become enthusiastic about Planck's deism, which omitted all reference to established religions and had no more doctrinal content than Einstein's Judaism. It seemed useful therefore to paint the lily, to improve the lesson of Planck's life for the use of proselytizers and to associate the deanthropomorphizer of science with a belief in a traditional Godhead.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ «Modern History Sourceboook: Robespierre: the Supreme Being». Fordham.edu. بایگانیشده از اصلی در ۸ اكتبر ۲۰۱۴. دریافتشده در 2010-07-04. تاریخ وارد شده در

|archive-date=را بررسی کنید (کمک) - ↑ «Reform Judaism and the relationship to Deism». Sullivan-county.com. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۰-۰۷-۰۴.

- ↑ Tatyana Klevantseva. «Prominent Russians: Mikhail Lomonosov». RT.com. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۲-۰۷-۱۰.

A supporter of deism, he materialistically examined natural phenomena.

- ↑ Ronald Bruce Meyer. «Napoleon Bonaparte (1769)». ronaldbrucemeyer.com. بایگانیشده از اصلی در ۶ ژانویه ۲۰۰۴. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۳-۰۲-۰۷.

His studies, says the Catholic Encyclopedia, 'left him attached to a sort of Deism, an admirer of the personality of Christ, a stranger to all religious practices, and breathing defiance against 'sacerdotalism' and 'theocracy'.'

- ↑ Talia Soghomonian (۳ اوت ۲۰۰۸). «Nick Cave». musicomh.com. بایگانیشده از اصلی در ۲ فوریه ۲۰۱۲. دریافتشده در ۴ آوریل ۲۰۱۳.

Asked if he's a believer, he replies evasively, 'I believe in all sorts of things.' I attempt to lift his aura of mysticism and insist. 'Well, I believe in all sorts of things. But do I believe in God, you mean? Yeah. Do you?' he turns the question on me, before continuing, 'If you're involved with imagination and the creative process, it's not such a difficult thing to believe in a god. But I'm not involved in any religions.'

- ↑ «Nick Cave on The Death of Bunny Munro». The Guardian. سپتامبر ۱۱, ۲۰۰۹.

Do I personally believe in a personal God? No.

- ↑ James R. Hansen (۲۰۰۵). First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong. Simon and Schuster. ص. ۳۳. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۷۴۳۲-۸۱۷۱-۳.

It is clear that by the time Armstrong returned from Korea in 1952 he had become a type of deist, a person whose belief in God was founded on reason rather than on revelation, and on an understanding of God's natural laws rather than on the authority of any particular creed or church doctrine. While working as a test pilot in Southern California in the late 1950s, Armstrong applied at a local Methodist church to lead a Boy Scout troop. While working as a test pilot in Southern California in the late 1950s, Armstrong applied at a local Methodist church to lead a Boy Scout troop. Where the form asked for his religious affiliation, Neil wrote the word “Deist. ”

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ June Z. Fullmer (۲۰۰۰). Young Humphry Davy: The Making of an Experimental Chemist, Volume 237. American Philosophical Society. ص. ۱۵۸. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۸۷۱۶۹-۲۳۷-۵.

In prominent alliance with his concept, Davy celebrated a natural-philosophic deism, for which his critics did not attack him, nor, indeed, did they bother to mention it. Davy never appeared perturbed by critical attacks on his "materialism" because he was well aware that his deism and his materialism went hand in hand; moreover, deism appeared to be the abiding faith of all around him.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Explorers Club, New York (۱۹۸۱). Ernest Ingersoll، ویراستار. Explorers journal, Volumes 59-61. Explorers Club. ص. ۱۰۵.

Nominally, Wernher von Braun was a Lutheran, but he was actually agnostic with atheistic overtones until the defeat of Germany. He confided to me that he seemed to have experienced a revelation. He had adopted the religious philosophy of Albert Einstein in which he did not believe in a God who punished the bad and rewarded the good. Instead, he believed in a Supreme Being responsible for the Universe and all it embraces.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Werner Heisenberg (۲۰۰۷). Physics and Philosophy: The Revolution in Modern Science. HarperCollins. ص. ۲۱۵. شابک ۹۷۸-۰-۰۶-۱۲۰۹۱۹-۲. پارامتر

|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ Werner Heisenberg (۱۹۷۱). Der Teil und das Ganze. Harper & Row. ص. ۸۴.

Still, religion is rather a different matter. I feel very much like Dirac: the idea of a personal God is foreign to me.

پارامتر|تاریخ بازیابی=نیاز به وارد کردن|پیوند=دارد (کمک) - ↑ «نسخه آرشیو شده». بایگانیشده از اصلی در ۲۹ سپتامبر ۲۰۰۹. دریافتشده در ۴ آوریل ۲۰۱۳.

- ↑ «Famous Deists». Adherents.com. بایگانیشده از اصلی در ۳ مه ۲۰۱۵. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۰-۰۷-۰۴.

- ↑ «Victor Hugo». Nndb.com. ۱۹۱۵-۰۴-۲۱. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۰-۰۷-۰۴.

- ↑ «Alfred Adler Biography from Basic Famous People - Biographies of Celebrities and other Famous People». Basic Famous People. ۱۹۳۷-۰۵-۲۸. بایگانیشده از اصلی در ۳ مه ۲۰۱۵. دریافتشده در ۲۰۱۰-۰۷-۰۴.